Run Toward The Sun: Remembering Juanita Rogers ia

supernatural Photo Memoir of Juanita Rogers, a black self- taught artist from the South . This

is a story about a African -American woman and a young priviliged white woman -both artists . Behind this double

biography is a soulful sub-text that acknowledges the force of friendship, and the fears and strengths that shape and change

the lives of not only these two women, but all of us. A story of two bold women, both who chose not to make safe

choices. One is rich and one is poor. Both are from the South, and both are artists. They become friends. Through their eclectic

friendship, each on their personal quest, they travel through their own rite of passage and

gain a better understanding of themselves and each other.-----a story woven with a curious thread...and the devil may

care duet of this unusual friendship is true. I first met Juanita Rogers more than thirty-five years ago, and became a frequent visitor to her home near

Montgomery. Over the years I amassed many hours of audio and video-taped interviews with Juanita Rogers

and her rural primitive surroundings, and photographed her and many of her creations. The

book is filled with Photographs and quotes from Rogers . The book also contains

one essay on Juanita Rogers and her work. Folk art scholar,Tom Paterson, has provided an art-historical appraisal of

Juanita's sculptures and paintings. Hers is a story of an incessant drive for creative

expression amidst poverty, social struggle, and tremendous physical disability. Anton Haardt SUMMARY Folk artist Juanita Rogers

was an uneducated black woman living in a dilapidated shack outside Montgomery, Alabama. She had a powerful creative talent

and mystifying spirit. Juanita´s crumbling sculptures were made of mud, moss and bones: frightening evidence of compulsion.

The hauntingfigures were part of Juanita´s stories of magic stones, nuns and graveyard dirt. Much defied logic. I visited

her regularly and eventually became her confidant and the mender of her mud creations. I choose not to dismiss her as crazy

but instead to explore the mystery of her creative drive. Our challenging climb to friendship continued til her death in 1985.The

two of us through our struggles transcended our barriers and together united to preserve and further Juanita's mission. Run Toward the Sun is

the celebration of this unique and obstinate artist and my quest to document and elevate her life´s work.

BEGINNING In the intense heat of summer in Alabama, my life

changed abruptly with a ringing telephone. While painting in my studio, a Social worker called seeking my assistance

with self-taught artist Juanita Rogers. Juanita , a dark skinned proud woan, lived in a dilapidated shack and was destitute

after the recent death of her husband. Her porch was filled with haunting clay sculptures: Ram men and Jungle women

that resembled the animal-man masks of the Ivory Coast of Africa. Intially she distrusted my offer of friendship

but through regular visits she slowly letting me enters enter her world, view her at work, and document her stories and memories.

We formed a pack: I would help her with financial assistance in exchange for drawings. MIDDLE I investigated her world and she gingerly unfolded to me her stories of carnival trains nuns

her illusory mentor , Stonefish. Her stories tangled my reality, and much of what she said contradicted and defied

logic. Mr. Stonefish was an enigmatic character and forever absents. Her sculptures were reminiscent of voodoo but she denied

any participation . The chronicles I made of her life was laddened with trails and our friendship was an uphill

climb in which often she would not cooperate. I doubted my job with her and its intrusion on my own life. My home had become

a mud hospital and my constant errands for Juanita took time away for my own artmakeing. Then in a strange twist one day she

pointblank asked me if I was Stonefish...Verifying that she had never really believed her own stories. Feeling somehow

that I could be her magic man , Mister Stonefish, and that she had trusted me finally gave me courage to

continue. ENDING Besides her constant money issues, she had an ongoing

health problem that she refused to deal with. She refused medical assistance. Not dealing with her health in a responsible

way eventually causes her health to deteriotrate and finally she was unable to live in the rural area unattended.

I reluctantly had to commit her to a hospital against her will or I knew she would die. This betrayal further unleashed doubt

or questions as to what I should have done .The responsibility was a burden. Shockingly even though she at first threaten

to blow of the heads of the doctors she quickly accepted her change and even seemed to enjoy the attention. Sadly

the cancer had spread to all her body. As her condition worsened she let me comfort her and be her caregiver. Finally

she trusted me. An abrupt end was coming and I sadly was losing my good friend. They lowered her casket into the red clay--the

dirt that she so loved. REFLECTION Juanita and I shared

an equal distrust of others , but in the end our Trust for one another

`prevailed. Juanita realized I appreciated her and her work. She showed me some of the primal spirit, so often lost today

in our modern world.... The rhyme of self freedom Uninterrupted by an overdose of intellect. By breathing life into her sculptures

and sharing them with me she symbolically revived herself and me. Juanita affirmed that through the process of creating one

can reassemble reality and conquer fears, dreads, and alienation and find strength in ones self. Art can be more than a pretty

picture to look at...also art can be nourishing and more important a powerful charm. |

Run Toward the Sun: Remembering Juanita Rogers By

Anton Haardt SATURNO PRESS PRESENTS

OUR NEXT BOOK! Run Toward The Sun: Remembering Juanita Rogers a supernatural true story of Juanita Rogers, a black self- taught artist from the South This is a story about a African -American woman and a young priviliged white woman -both artists . Behind this double biography is a soulful sub-text that acknowledges the force of friendship,and the fears and strengths that shape andchange the lives of not only these two women, but all of us. A story of two bold women, both who chose not to make safe choices. One is rich and one is poor. Both are from the South, and both are artists. They become friends. Through their friendship, each on their personal quest, they travel through their own a rite of passage and gain a better understanding of themselves and each other.

It is a story woven with a curious thread...and the devil may care duet of this unusual friendship is true. Juanita Rogers born near Montgomery, Alabama, in 1934 began "making mud" as a child. Using

cast-off materials and easily found material such as mule and cow bones, fossil shells, and mud dug from the woods near her

house, her primitive existence was reflected in her work. Although Juanita firmly denied any connection with voodoo or hoodoo,

perhaps in her work she unconsciously nurtured a dwelling place for a spirit, giving it an identity and personality. She

treated her mud work with an unwavering sense of mission, even though her eccentric ways and compulsive urge to create segregated

her from the outside world. A select retrospective of Juanita Rogers' work is planned in the near future, and

the book Run Toward The Sun: Remembering Juanita Rogers by Anton Haardt will be published soon. Saturno

Press is looking for a Distributor for the upcoming book. Juanita Roger's work has been accessioned by museums in the United States and

Europe, including such prominent collections as L' Aracine Museum in Paris,the Art Brut Museum in Lausanne, Switzerland and

the Outsider Archives in London. Her sculptures and drawings began to arouse interest even before her death, and knowledge

of her story has increased every year since. Baking in the Sun (1982) and Retrieval: Art in the South (1984) were among the first exhibitions to highlight her work. As

interest in the “mud woman” increased, her works became more sought after by private collectors as well. She was, for example, one of the celebrated artists included

in What It

Is: Black American Folk Art, a survey of the private collections

of the folk art scholar Regenia Perry (1982) and Parallel Visions, a touring exhibit of the Rosenak Collection

(1995) Juanita’s work has garnered the acclaim

of many collectors and curators. Her work was included in such exhibitions as: Baking in the Sun: Visionary Images from the South (1987) Curator Sal Scalora’s Women of Vision: Black American Folk Artist Gifted Vision: Black American Folk Art (both 1988) Passionate Visions of the American South: Self-Taught Artists from 1940 to the

Present, assembled

by New Orleans Museum

of Art Curator Bill Fagley (1994) Andy Nacisse’s Mojo Working (1999) Are We Alone (2000) American Visionary

Museum Exhibit of Extraterrestrial Visions.

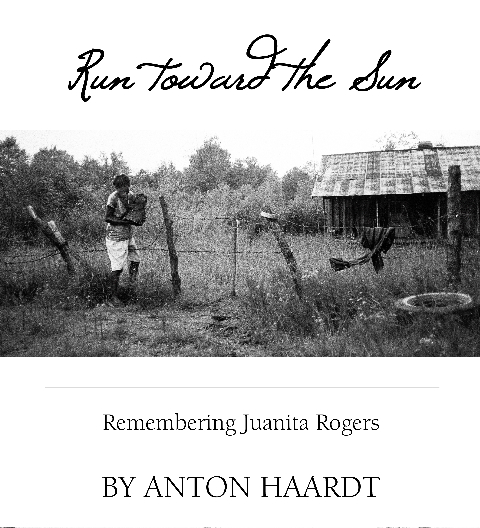

| Juanita Rogers Photograph By Anton Haardt

|

| Juanita Rogers Photograph By Anton Haardt

|

| Juanita Stonefish Sculpture

|

|

|

THE ART OF JUANITA ROGERS

From

Jude Schwendenwien’s “Aetna’s ‘Women of Vision’ Shows Distinctive Variety of Folk Art”

(The Hartford Courant: Sunday, July 24, 1988):

Juanita Rogers (1934-85) lived in an isolated, poor life in southern Alabama. Her

TV set was constantly on. Each picture represents a highly personalized, idiosyncratic takeoff on various

TV characters and themes. From her hysteria-induced poker game titled “Card Gamer” to “Camu Head,”

an eccentric interpretation of the Coneheads from “Saturday Night Live,” Rogers’ pieces show humor and heightened

imagination.

From What It Is: Black Folk Art

from the Collection of Regenia Perry. Catalog by Regenia Perry. Exhibition held at Anderson Gallery,

Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. (October 6-27, 1982)

The world of Juanita Rogers is essentially a world of make-believe. She

insists the driving force behind her creations is a creature whom she calls “Stoneface” and “Stonefish,”

who commands her to make art which he buys and over which he has supernatural powers. This frequent visitor to

Rogers’ house has never been seen by her neighbors and is undoubtedly a figament of her imagination.

The categories of Rogers’ artistic expressions are numerous. Her

earliest works were mud sculptures, which she still fashions, and calls “funny brick.” Animals, humans,

and apparent combinations of the two are modeled from clay quarried from fields outside her house. These mud sculptures,

which she considers her primary mission, are bold and vigorously expressive with seemingly exaggerated genitals. The

figures are reinforced with mule and cow bones, fossil shells, glass, Spanish moss, and embellished with mule teeth. Boxes

of mule teeth and animal bones to be used in future projects are stored under her bed and on the floor of her home studio. Since

unfired mud is an impermanent material, Rogers constantly remodels her sculptures, sometimes changing their appearance completely. The

surfaces of her funny brick sculptures are left rough and unpainted.

Rogers has also created

a number of eccentric, recycled yarn objects which initially resemble articles of children’s clothing. Unraveling

yarn from old sweaters, Rogers wraps the yars into a matted material and resews it to create socks, sweaters, and booties

which appear intended for wearing. Upon close scrutiny the tops of the booties and socks and the arm and neck openings

of the sweaters have been sewn closed, making them impossible to wear. The purpose of her knitting is unknown.

The third category of art forms created by Rogers is painting executed in tempera on paper, cardboard, and most recently

in oils supplied by her dealer. A prolific painter, she rarely repeats a subject. Some of her earlier

paintings are single figures on sheets of gray paper with a rugged simplicity using a fluid impasto technique. The

most striking features of Rogers’ figures, both human and animal, are the large eyes which appear to project from the

paper and exist apart from the faces to which they belong. The figures in her paintings are strong, simple statements. Although

there is no actual attempt to model form, there is an occasional change in values of colors, and the outlining of some of

the figures in contrasting colors or tones results in a suggestion of three-dimensional form.

Rogers’ current

paintings are larger in scale than earlier works and while most of the subjects appear to be figural landscapes, the iconographic

content is not always readily definable. Among the more accessible in this collection are a girl under a pear tree,

a wife confronting her husband with a broom, a couple drinking in a bar, and a marvelous self-portrait of Rogers in an outdoor

setting with her pets.

SAMPLE CHAPTERS OF RUN TOWARD THE SUN

CHAPTER 1

A SIRIUS CALL

| Our first meeting was in one of those lethal stretches we call “dog days” in the

South, when the heat and the humidity make you sweat non-stop. “Dog days” come near the end of summer, when the

dog star rises at the same time as the sun, when flies, mosquitoes and gnats swarm, when the eerie drones of cicadas fill

the air. Twice a week during this time of year, the bug-sprayer truck made its rounds through the neighborhood where I lived

in Montgomery, Alabama. |

In those broiling days the wisteria bloom in lilac color, and the night-blooming cereus unfold with fragrant

petals after midnight. The cereus pay a yearly ritual homage to the dog star Sirius. My ancient mother sets her alarm for

the event and invites her relatives and friends into the darkness to view the spectacle. She even tried to convince the local

television stations to give the event live coverage, but they did not take her suggestion seriously.

I was born and raised in Montgomery. By 1980 I had lived away for many years. After finishing

college in California, I spent the next decade traveling for months at a time in the Caribbean, Europe, and South America.

Between my trips abroad, I lived in a string of American cities including Atlanta, New Orleans, Houston and New York. I even

then had a growing interest in self-taught artists. So, by the time I’d reached my early twenties, I was yearning for

a real home. I needed a place to paint in peace and to regroup, so I decided to settle in Montgomery, near my mother.

In those times there was a lot about Alabama that made me

uneasy, and often embarrassed, but I was glad to be back there, in my Victorian house with its clean water, electricity and

modern conveniences. I was happily working on a large painting of a mermaid, my small black and white television tuned to

a CBS special on the failed rescue mission of the US hostages in Iran. I turned away from the news of crashing helicopters

and returned to the mystery of the mermaid gliding through the sea on my canvas. I was approaching a state of serenity when

the telephone rang.

“Is this Anton Haardt?”

said the voice.

“Yes.”

“My name is Virginia Boone. I’m a social worker. I read in

the newspaper about how you promoted the work of Mose Tolliver, the folk artist. I’m trying to help a woman who makes

sculptures. I thought you could give me some advice.”

“Maybe,” I said. I didn’t expect much but I felt obligated to sound polite. “What kind

of sculptures does she make?” I asked.

She

just said “sort of clay figures. With bones.”

`The

woman’s husband had died recently, Mrs. Boone explained, and left her with no means of supporting herself. She told

me that the woman clearly needed help but wouldn’t accept it. She even refused to apply for food stamps or government

assistance programs.

“I know this may sound strange,”

Mrs. Boone continued, “but she says she already has a job making these mud sculptures…her work doesn’t

bring in any money. Would you come with me to meet her?” When I’m painting, I hate to leave the house, but I was

curious about this lady’s sculptures, and said I’d go.

“Is tomorrow afternoon all right?” she asked.

I said that would be fine.

In the late

1960s I had befriended the self-taught artist Mose Tolliver, an elderly black man in Montgomery who had been selling his pictures

for as little as five dollars a piece. He had enormous talent and I persuaded him to let me find a few art dealers and collectors

who would embrace his work and provide better pricing helping to boost his career. I was not looking for more folk artists

to help, but as an artist I’m always intrigued by the works of untrained, “outsider” artists and the sources

they draw upon.

Back to the table and the progress

of my mermaid…the colors were still wet. I began swirling and smoothing more blues and greens, and before I knew it

the image, measuring thirty by forty inches, was done. I’ve always believed that when I am in harmony with a painting

that I can reach a state where magic things unfold. Could that phone call have been a conduit to such a state?

The next afternoon Virginia Boone came in person. She looked

to be about fifty-five, a gray-haired woman wearing a conservative oxford shirt, khaki skirt and loafers. Inviting her into

my studio, I showed her some of my own work and paintings by Mose Tolliver, whose work was now becoming accepted in mainstream

gallery and museum circles up East. She murmured appreciation for the images all around, which made me pleased, and then we

set off on our trip.

Mrs. Boone’s station wagon was

neat and orderly inside, unlike the inside of my Volkswagen van. As we drove south from Montgomery she said, “I’m

glad you could come with me. I didn’t know who else to call.”

“Where exactly are we going?” I asked as some familiar landmarks went by.

“It’s out past Snowdoun a little bit.”

She turned down Norman Bridge Road and onto US Highway 331.

“It’s out near Ramer, actually.”

She told me that she did not know much about Mose Tolliver. “But I’ve read about

him. He’s a primitive, right?” she asked.

“There’s

lots of names for what Mose does. The term really is folk artist, or outsider artist. But he wasn’t trained in school.

Self taught artist is another way of putting it.”

“That’s

what Juanita is, I guess. She’s an outsider for sure, but I don’t know if you would think she’s an artist

or not. Juanita Rogers is a very unusual woman. After her common-law husband died, she was alone out in their rural shack.

One day I made a routine call to see if she’d sign up for welfare. Says she works for a man named Mr. Stonefish. But

there’s no sign of money coming in. And no sign of this Mr. Stonefish either. She needs food and financial aid. She

can’t care for herself and I’m really at a loss to know what to do. Maybe you’ll have some ideas.”

Mrs. Boone began telling me a little more about the sculptures.

Though, I was still unclear what role I could play in all this.

“ Juanita digs up clay from around her yard and makes these animal statues. Maybe you’d call them

that...”

We drove into a quiet rural area near

Snowdoun, passing fields, clapboard houses and bullet-riddled Coca-Cola signs. Spanish moss hung from the large oak trees

mixed with pines along the road. Every mile or so stood a small white church, its yard swept clean among green fields slowly

parching from the summer sun and lack of rain. Cattle and horses grazed in the shade of large oak trees, and grapefruit-sized

mock-oranges littered the pastures. Home -made fish ponds lay near abandoned barns and rusted tin-roofed shanties.

Soon we turned off the main road by a church and a cemetery

overgrown with moss-covered bramble vines. “How did you ever find her place?” I asked, marvelling.

“Oh, I’m used to travelling out these country

roads. It’s my job.”

She pointed out a fresh marker among

a group of drab gray tombstones entangled in wild rose-bush. “Her husband’s buried over there; he died about two

months ago.”

Brambles scraped the bottom of the

car as Mrs. Boone steered onto a narrow dirt path through a field. She stopped to open a gate and we drove into what once

had been a cow pasture, but now was knee-high with weeds.

“Here’s

the turnoff. We have to walk the rest of the way.” Mrs. Boone pulled up the barbed wire for me to pass under.

“Careful not to rip your blouse.”

“Does this woman have a car?” I asked.

“No. She’s just out here in the pasture. You’ll

see.”

I bent under the barbed wire, thinking

to myself how other, smarter people were no doubt comfortably nestled in air-conditioned living-rooms, sipping a cool lemonade.

Yet, even as I looked over the rusted barbed wire, feelings stirred of some strange familiarity at the sight of Juanita’s

place.

A weathered shack with a red rusted tin roof and unpainted

clapboard siding set in the middle of a field under a pine tree. It looked like a club house, built from scraps and patched

with whatever was on hand. A dented zinc wash tub, a pair of muddy black rubber boots and two plastic buckets filled with

dirt were out in the yard. A lone bob white call signaled our approach and all the while the cicadas droned in the heavy heat

of the afternoon.

Getting closer, my eyes took in about

a hundred smashed aluminum cans and old soda bottles on the porch. Beside the cans were an old muslin pillow case full of

broken glass and a gunny sack stuffed with Spanish moss. An old splintered board propped up the front steps. Leather scraps

from an old saddle hung from a nail on the side of the house. Slowly my eyes came to rest on a cluster of monstrous, crumbly

mud sculptures arranged along the porch. They were like creatures from another dimension: ominous animals of all shapes and

sizes, with powerful expressions, stark against the grey weathered boards. One or two figures looked complete; others appeared

to be in a state of becoming.

Before I really could investigate,

Juanita peeked from behind the front door decorated with a good luck horseshoe. Opening the door fully, she ventured out,

her bare feet carefully avoiding the muddy debris scattered everywhere.

Juanita Rogers was a striking, dark skinned woman, thin-limbed and sinewy, standing only about five feet tall.

She had high cheek-bones and wore a red bandanna low over her forehead. Her hair was in tightly braided small corn rows. I

figured her to be about twenty years older than me--somewhere around fifty. Noticing a slight bulge in her midriff, I wondered

if she had suffered an abdominal rupture of some kind.

“Good

afternoon, Mrs. Boone,” she said, eyeing me as she spoke.

She wore a faded yellow cotton moo-moo. Her skin was like velvet in the sunlight. Her dark eyes darted nervously.

She had an unusual beauty. She nodded to me ever so slightly and said “Hello.”

I said hello and gave my name.

A few dirt daubers were buzzing around the rafters. She looked up at the insects in their mud nest, and grinned.

“Theyse’ been a working all day roun’ here...and using all my mud!”

I laughed, hoping to generate some kind of contact.

Mrs. Boone said, “Anton has come with me to visit and look at some of your mud sculptures.”

Juanita stood aside to allow us through the doorway, yet,

I couldn’t help feeling that we were invading her privacy.

Juanita’s front room was dark and smelled of burned logs and old ashes. The window panes, smoky black,

showed years of fireplace soot. She didn’t offer any niceties or make eye contact with me, though she showed us into

her work room--and more of her pieces. The space felt like some mysterious cave. My eyes had to adjust to the strong sunlight

when we came outside. Even though I had so recently returned from palm-roofed lean-to’s in Ecuador, where the main street

was nothing but a dirt path and the hospital was merely a closet-sized room, I was overwhelmed by the primitive disarray of

Juanita’s home.

Mud sculptures were everywhere. The

furniture, as if plucked from a junk shop, was rickety and rusty. In one corner, a pile of pure dirt had been dumped on the

floor.

Two sculptures of horned deer men stood out, like the

kings in an eccentric set of oversized chess pieces, each one about two feet tall. They were full of power.

“I had in mind a man sitting on a stump for that one,” Juanita

murmured.

“Some man, he is!” Thinking

I’d hate to encounter him some dark night when I was alone.

Several of the crude sculptures looked like devils with rams’ heads. They were eerie…not at all

the pretty what-nots Juanita had described to Mrs. Boone. They were monsters of mixed antlers and deer skulls, covered with

mud, and had a fetish-like quality.

Juanita had

sculptures stacked everywhere: in open suitcases, crowded onto a TV tray, on a rusty metal table. The mud was crumbling. A

lot of dirt and debris lay strewn over the floor and table. All were unlike anything I had ever seen.

“These are wonderful pieces,” I said in awkward admiration.

“Yes’m?” replied Juanita as if it were a question.

She was nervously fanning herself with a rag, clearly on her guard. She seemed curious as

to my interest in her and her sculptures, peering at me secretly before looking away as if she didn’t want to appear

too interested.

This woman’s haunting sculptures…summoned

a sense of awe. Her pieces were the work of someone in the grip of intense compulsion…crude and scary. Another devil-like

creature with bulging eyes of clay balls and real animal teeth glared straight ahead at me. A bleached white cow femur protruded

from the head of another sculpture. Each sculpture was more eerie than the next.

A ray of afternoon light streamed through one cleaned pane onto a clay animal. His terra-cotta

body was compact and comical with expressive eyes and a large bill. I asked her what this animal was.

“A Duck is a Duck--it goes quack,” said Juanita.

Giggling nervously, I asked Juanita about how she had started making such sculptures. She

glanced toward the wall and muttered something unintelligible. I began to understand why a social worker was buffaloed: this

woman was an enigma.

Juanita led us around, showing off

more of her mud pieces hovering over her sculptures as a mother would dote on her babies. In what I guess you would call her

“living room,” about twenty or thirty mud sculptures of all shapes and sizes crowded everything else out. The

rickety 1950’s enamel kitchen table held a satchel filled with more mud sculptures and crumbling dirt. A naked, flesh-colored

plastic doll, its eyes tilted into the back of its sockets, leaned against several small, dusty dog sculptures and a life

size cat made of red clay.

Juanita’s bedroom was dusty

like everything else. Two old iron beds covered with tattered quilts filled most of the room. I sat on the edge of one bed

and Mrs. Boone took one of the only two chairs. Juanita chose to remain standing. I saw a collection of bones in a shoe box

under the bed. Animal teeth were in the box and I asked her where she found all these curiosities.

“Just bones and teeth from out in the pasture. I use it for the mud. I use it for the

eyes if I want to. I chip the bones and teeth up sometime too.”

“Ms. Boone said you had a job making these pieces and someone comes to your house for them,” I said.

“Yes’m, I works for Mr. Stonefish. He comes when

he wants to.” She looked out her door as if to stop our conversation. Then she added, “Miz Boone has helped me

a whole lot. She brung me some peas. I sho’ appreciates what she done.”

We made small talk for a while, and then Mrs. Boone said we had better leave before it started

to get dark. As we walked out, I asked her if she would let me take one small mud sculpture home to look at more carefully.

“I couldn’t do that. You might take this mud piece

to prove I’m crazy or something!” She waited to see my reaction. I could understand her concern. She didn’t

know if we were there to help or harm her.

We

said our good-byes. “Thanks for letting me visit, Juanita. I feel lucky to have seen all you clay

sculptures. I hope to come see you again. Okay?”

“Yes

ma’am.”

“I’ll talk to you again

soon, Juanita,” said Mrs. Boone as she accompanied us a few yards beyond her porch.

As we walked away, I waved good-bye.

“Bye, now,” she called out. “Ya’ll be careful going home.”

It was at that moment I decided I wanted to get to know that woman. How--why--did she make

her world?

On the ride back to Montgomery, I

realized how sensitive Mrs. Boone was. Mrs. Boone had the compassion and insight to approach Juanita as

a person, not just a number in the bureaucratic files. Other social workers might have dismissed Juanita as crazy and taken

steps to have her committed.

Mrs. Boone realized Juanita was an

eccentric woman even though her sculptures looked like nothing more than strange, ugly piles of dirt in other people’s

eyes.

“I just had a feeling that there might be something

to this all,” she said. “I hope something will work out. May I call you after you have had time to work all this

out?”

“Of course, “ I said.

“I’ll try my best to find some way to help,” but I had no idea what I could do. I guess I was too shocked

to think.

Getting out of the car, I thanked

her twice.

Back in my studio, I let my mind drift

about Juanita. Something was pulling me to know more about her. She seemed to be totally ruled by her incredible urge to create.

I had begun collecting the work of other self-taught artists but was unclear how I could assist Juanita; she seemed so detached

from everyday life. Her art, if that’s what it was, was so impermanent.

The next day I talked to Mrs. Boone on the phone. We hoped that if we could get Juanita to work with us, that

she might eventually agree to accept some form of social aid. Juanita had told Ms. Boone she already had a job working for

some man named Stonefish, but she was several months behind on her rent and had no money for food.

I offered to pay her rent and to cover several bills she had accumulated in the months since

her husband’s death. In exchange for my help, we hoped she would agree to enroll in the federal food stamp program.

Throughout the next few months, Virginia Boone continued to work with Juanita, periodically driving out to Snowdoun to check

on her.

I began to visit her on my own.

CHAPTER 2

THAT’S HOW SHE LIVED

| Her bathroom was the cow pasture. The house had no pipes. Her only source of water was rainwater, which she collected

in a big bucket placed on the ground below her roof. For heat, there was an open metal oil drum in which she burned wood and

paper scraps. One bare light bulb hung from a fixture in the center of the ceiling. A small back room in her house had a little

bed and another drum for making a fire. |

Even after having visited the homes of many black people, some of them very poor, nothing compared to such squalor.

At the back of the house was another room she referred to as the kitchen. It looked unused: a few pots and pans were scattered

on the floor. An old, bent floor lamp with one light bulb stood in a corner. A defunct refrigerator was rusting in the center

of the room. Juanita had decorated this appliance by painting a large, frightening monster on the door. The large eyes and

a huge snaggletoothed mouth made it look like a creature out of a horror movie. Yet the monster refrigerator was only some

kind of weird icon to decorate Juanita’s kitchen. There was no sink or counter space in that kitchen. There was a large

freezer that took up almost the space of the room, but she had nothing to freeze inside it.

Juanita lived with her mutt Wolf, her tomcat Brenda, and a pair of obese pigs she raised in

a small pen near her house. Her neighbors Levi and Queenie Huffman and their son, Johnny, came over occasionally and sat on

the porch to pass the time of day. Several children who lived nearby also visited her on occasion, and they made small clay

sculptures with her. The kids were curious about Juanita and seemed to enjoy hanging around.

The only other person I ever saw at her house was a man with a big scar on the front of his

head. Juanita explained to me that he had been hit in the head with an axe. The scar and an indentation in his forehead gave

him a foreboding look. He wore overalls and a hat with a picture of two pigs screwing under the embroidered motto “Makin’

Bacon.” He never said a word; I got the impression that he might have been mentally disabled by his mishap with the

axe.

He did not seem intimidated by Juanita’s scary

mud sculptures or suspicious of her eccentric ways. Maybe they were lovers. Although Juanita told me that he occasionally

stayed in the back room, he left when he knew I was coming. I guess the ‘Axe Man’ was the source of whatever food

kept her alive.

One day, after visiting Juanita regularly

for a couple of weeks, she beckoned me into her kitchen and proudly announced, “Miss Anton, look at this!” She

opened the freezer door to reveal a pig, skinned pink and frozen solid, feet and all. “I butchered him myself,”

she boasted.

One look into the freezer made me

feel I was viewing some distorted freak specimen at a circus side show. There, encased in ice, was this pink, shriveled swine,

his skin a bluish-white with rose-colored folds, his eyes frozen shut by the ice on his eyelashes. The pig was jammed in a

corner of the sides of the freezer, frozen stiff in a fetal position.

“Hmm, Juanita, you’ve got quite a meal for yourself.”

She smiled proudly, “I fattened him up first, ‘til that piggly wig was good and

plump.”

She kept him in there for weeks, but

would unplug the freezer at intervals so that he thawed, and then she refroze him again for a while; especially when she knew

she would be having company. I wondered if the pig was serving as inspiration for the wild mud monsters she made.

At that time I still didn’t know Juanita very well.

Mrs. Boone and I were both worried that she might actually try to eat the pig. Mrs. Boone decided to call the county health

department and have them take it away as a health hazard. The health department finally came out and ordered Juanita to dispose

of the pig. Juanita didn’t like that because she was so proud of her pig, but they took her pig anyway.

After that, Juanita killed her other pig and preserved him

in salt brine. His dried, flattened head had a long string wrapped around the neck. His ears were intact, and the hair was

still on his eyelashes. She had cured him in the salt brine, then dried him out, his entire body pressed flat, as if a truck

had run over him. Maybe she was saving him for winter when she might cut off a piece and cook it in a pot and use it for soup

or something. Some old country folk still ate this way. I don’t know whether she intended to eat him, but she was sure

proud of him. She had him hanging up from the rafters of her front porch. In one of the photographs I took, she is posing

with the dried corpse, beaming proudly as if she were holding a bouquet of lilies.

One afternoon we were sitting inside her little house when it started to rain. The raindrops

made melodic plangs on her tin roof. In that dimly lit room, amidst the disarray of dozens of crumbling clay sculptures, I

asked Juanita to describe what she did on an average day, from the time she first woke up until she went to bed at night.

She looked off into the room as if she were trying to remember,

and then said: “Well, first, when I wake up at about five in the morning, I thank God for another day. Then I go over

and put the coffee on the fire, right there on the pot-head. Then I get the duster and I begin to dust a little.” She

went on to describe a version of an “average day” that bore no relation to what I had witnessed of her life. There

was no duster. Dirt was everywhere. It was as if she were relating a day in the life of a housewife on one of those 1950’s

situation comedies. Maybe that was the life Juanita imagined she lived, or the one she wanted me to think that she lived.

Or maybe she was just entertaining herself with a story. She said it all with a very straight face, telling me about her day

of cooking and housecleaning as she stood in a room so cluttered with dirt that you would need a shovel to clean it out.

“Then I prepare my list of chores for the day and what

I’m going to serve for my meals.” She had no stove, no dining room table and I’d seen only a few plates,

forks or spoons. Once, she’d served me some turnip greens and cornbread, both cooked in a cast-iron pot over an open

fire.

I asked her what she liked to eat. She said, “Maybe

today I’ll have fried chicken.” (Of course there was no means of refrigeration even if she had chicken, since

the refrigerator didn’t work, and the freezer was only used to impress the occasional visitor.) “First I cut up

my chicken. I put me some coffee on at the fire and sit down and drink it. Then I might do some more housework or something.

I sometime watch TV or listen to the radio. Then I start to working on the mud a while.”

She asked me on several occasions if it would it be possible to have a washing machine installed

in her house. The problem was that she had no running water. I tried to explain that the water had to come first and without

it, a washing machine wouldn’t function. She didn’t want to think about that. She just wanted a washing machine,

period. At last she changed the subject, without really giving up.

She had made a unique mud piece that she described as an electric coffee pot. “This is used for the businessmen

when they have a convention,” she explained. “When the businessmen don’t have time to stand in one line,

this way they can have two lines and move on through quicker to get their coffee.”

“It is totally electric,” Juanita insisted.The ‘coffee pot’ was actually

a surreal, crumbling, mud sculpture, built around a central cow pelvis and embedded with teeth, Spanish moss and mule hair

sticking out in all directions. The hollow interior of the cow pelvis created a vessel. She had equipped it with two spouts

to expedite rapid service. The coffee supposedly would pour from each spout so that the businessmen could move through the

line, she explained.

Juanita also showed me some of the

handmade clothes she had done for children. Sets of hats, jackets and gloves re-sewn from old discarded sweaters had been

reworked into these padded creations. About three or four sets of hats, jackets and gloves lay neatly folded in the corner

of her room. They were stacked up alongside numerous other piles of dusty things.

Even though she was living in hot, humid Alabama, she had made these clothes with thickly

padded layers sewn together as if they were for people living in Siberia. The proportions were way off: the openings for the

gloves, for instance, were the right size for a baby while the fingers were adult size. The shoes would have fit a baby’s

feet but the soles were padded with so much cotton that a baby would have tumbled over at its first step. There was no doubt

that the results of her creative ideas were ingenious, but they were so skewed that using them would have been impossible.

“Juanita, these are great!” I said. To me id did

not seem to matter its ???. As an artist I could sincerely appreciate her obsessive ???? its strange beauty.

“No ma’am, this ain’t nothing, is it?”

“Just look at the way you’ve reworked the big

arm sleeves for a child and then added on the gold trim,” I went on encouragingly.

“I just took those old sweaters the rats were eating on. I didn’t know much how

to sew. But I thought it was nice to keep the chillins warm in the cool weather, Miz Anton.”

“Miz Anton” is what Juanita insisted on calling me despite my early protestations.

For black women of her generation, raised in poverty before the Civil Rights movement came to liberate us all, calling young

white women “Miss” was a habit few of them could shake. I decided that if Juanita finally felt me trustworthy

that perhaps she would drop the “Miss.”

The

distinction between reality and fantasy meant nothing to Juanita. She created and recreated her day-in-the-life as she saw

fit, but I yearned to know the real truth. She had plenty of answers; I just didn’t know which ones were real.

Slowly, after many visits to Juanita’s house, she began

warming up to me. I usually brought her food, cigarettes and other supplies, and as we sat and visited for hours, I tried

encourage her to talk more about Stonefish. I gathered that he lived near by, but I never encountered him. Juanita’s

neighbors said they knew nothing about Mr. Stonefish. In fact, they were doubtful he had ever really come to Juanita’s

house.

During one of my visits, we were on her porch, and she

was working on another mud sculpture while we talked. Juanita’s next door neighbor must have seen my orange Volkswagen

van in front of the house and, probably out of curiosity, came over. Queenie, in her late sixties, was dressed in a brown

plaid summer dress and white bedroom slippers with a pale blue scarf wrapped around her head.

“Hot enough for y’all?,” she asked in a friendly tone. She sat down in the

rusted porch chair and started to fan herself. She folded her legs primly under her chair, letting her eyes wander over the

mud sculptures on the porch. “Oh, Juanita, these are so pretty!”

Juanita was working on a deer-horned piece. Glancing over at me, Queenie peered over the tops of her gold wire-rimmed

glasses. “I was just telling Juanita yesterday, I wouldn’t know where to start to make something like this. Look

at that one, he got toes on him, like a little dog or something. And that one’s got real teefies, don’t he? “

Giggling nervously, she asked: “Now what you call this one, Juanita?”

Juanita raised her eyes from her work, as if she knew her neighbor was pretending interest

for my sake ??? didn’t think much of her sculptures. “That’s the funny brick, Queenie,” she replied

matter-of-factly, continuing to brush mud onto her fanged, two-horned ram man.

To pass time, I asked Queenie if she had ever met Stonefish. She looked a little befuddled.

“Well, he’s never been out here, not while I was around.”

Juanita looked over at Queenie with dismay. “He’ll come out to get this all when he gets ready.”

“Maybe he done disappeared, Juanita.”

“Queenie, he ain’t done disappeared,” snapped

Juanita.

Queenie turned to me. “I know she done been trying

to call him, Miz Anton.” She sympathetically patted Juanita on the back and said: “I sho’ would try to get

in touch with him if you could, cause you really need something now, Juanita.”

A bob-white called in the distance, adding a plaintive note to the conversation about the

elusive Stonefish. Juanita’s tomcat, Brenda, jumped up in Juanita’s lap. Queenie indicating Brenda, asked “Juanita,

ain’t her mate that black cat?

Juanita, clearly

irritated by her neighbor’s questions, curtly corrected her. “Brenda’s not a girl cat. She’s a tomcat,

Queenie.”

Brenda purred as Queenie patted his

brindle-colored fur.

Juanita began discussing the sculpture

she was working on. “This one is made from mule bones. It’s grass, weed, and shells. It’s a monster--a monster

man.”

Queenie edged closer and touched the

deer-horned sculpture’s nose. “Hello, Monster! You sure look like a monster.” Queenie swatted a buzzing

fly as she turned to watch Juanita work. “Oh, that looks so nice, Juanita.”

Juanita frowned as she smeared red mud on the tip of her “monster-man,” ignoring

Queenie while concentrating her convoluted explanation of her art’s connection to Stonefish. “See, they calls

it the funny brick. I call it mud. That’s not my brick. That’s the piece I made. I didn’t create this ...

not like...like...they discover electricity. I made the piece for Stonefish. Stonefish, they call him. I don’t know.

Maybe it’s the name of a place, or maybe it be him. I don’t know.” For a moment she seemed as puzzled as

I was. Then she said, “Stonefish could turn these things into most anything he wanted. If a cat was on one side, he

could make the same shape the other.”

Juanita

adjusted the red bandanna on her head and threw a gaze at Queenie and me. “I don’t see how he done that.”

Neither of us knew how to respond.

Juanita continued:

“See, I used to get me a little box, a pasteboard box, and I’d put two or three mud pieces in it. I’d put

‘em out there in the mail box for the pickup. I was sending them in the mail, two or three smaller ones. They was smaller

than what I’m making now.”

Juanita abruptly

dropped the subject of Stonefish. As she layered mud on the new monster, Queenie and I sat quietly, making occasional small

talk when Juanita spoke, but otherwise maintaining a respectful focus on what Juanita was doing.

Somehow Juanita’s world challenged me to rethink many assumptions I had made about her.

Whenever I imagined I’d come to understand a little about her, she’d throw in another twist. One day, driving

to her house, I pulled over to gather some blue periwinkles and an arm-full of brilliant yellow Goldenrods. But when I gave

the wildflower bouquet to Juanita, she looked at the blossoms as if they were unwanted step children and said, “Miz

Anton, them ain’t flowers. Them ain’t nothin’ but weeds.”

Blushing, I realized there was more to learn.

CHAPTER 3

WHERE I’M COMING FROM

| What I came to know about Juanita and the way I connected with her are so intertwined with pieces

of my own life that it’s impossible to tell her story without reflecting on some of mine, too. I saw Juanita through

my lens: the eyes of a privileged hard-headed white woman who grew up in the South during racial segregation. |

Although Alabama is my birthplace, I never felt I belonged

there. As a child I fantasized that I was a voyager from another planet and that I had accidentally fallen out of my spaceship

into a Southern terrain.

My father was a realtor-developer.

He built the neighborhood we lived in. He named a street, Anton Drive, after me, his only child. We lived on the corner of

Anton Drive and Haardt Drive, in Haardt Estates. Still, my whole life has been spent trying to find out where I did belong. This quest has taken me to the Amazon jungle,

the Pyrenees Mountains, a Mexican jail, a VA Hospital, and some interesting places in between.

Ever since childhood I’ve wanted to salvage and save. I found validation in administering

aid to stray dogs and lost people or objects that I could mend and make new. I was a mender, a saint of “lost balls

in the high weeds,” as my Aunt Ruth used to say. That was her way of describing those people who had a hard time finding

their way through life.

When I was twelve I had a horse named

Charlie. He’d been put out to pasture after a trailer accident, diagnosed to never again jump in competition. Somehow,

by luck and defiance, he and I both surprised everyone when we won the state Jumper Championship Award. After that, I successfully

rehabilitated several disabled horses, managing to keep them from the glue factory. I even succeeded with a few friends and

lost relatives along the way.

For twenty years a tattered barber

chair had sat in my father’s basement, destined for the junk yard. Today it shines in my living room, restored with

new chrome. And, I kept mending my son’s ripped blue jeans until he complained one day that no one else wore patched

jeans; could we please throw them away. To this day, I can’t stand to see something discarded that still has life.

Maybe my salvaging obsession is because I feel so few people

truly appreciate the intrinsic beauty of people of objects. Maybe I paint an homage to a person or thing to restore its lost

beauty.

In my own paintings, I combine broken pottery, sea junk

and paper scraps and make them in a “portrait” to give all of them a second life and more recognition. It is like

creating order from chaos, travelling through portals into other worlds, not knowing what might be found. Scraps of torn paper,

pirated images and objects are reassembled as I hope to conjure some talismanic message of truth in the final creation.

It is said that the birth experience makes a big imprint on

one’s psyche. My particular birth marked me with a spirit of determination. My mother told me, when I was born in October

of 1948 that I just would not come out from her womb at first, even after the doctor in the delivery gave her a shot to hurry

things up. My mother was in labor many hours when I pushed one shoulder out. That was as far as I got. The birth process came

to a standstill. By this time, my mother was exhausted, her heart beginning to weaken. Worried that she might not survive,

the doctor asked my father which one of us should be saved.

“Save my wife,” my father replied. As they were preparing to do me in, I shot right out. And so

my life began.

My mother, Mabel, whose maiden name

was Brantley, came from a family of 14 children; they were brought up in rural Alabama according to the strict codes of the

Holiness Church. Their parents held regular religious meetings in their home. Mama wasn’t a particularly willing participant.

She told me she remembered one such session at which the children were all expected to be rapt in the Spirit and speak in

tongues, but she found a way to slip out the back door before it was her turn.

When she was in her early thirties, my mother went to work as a secretary for a tombstone

manufacturer. One day my father stopped into the tombstone shop where he caught a glimpse of my mother’s black hair

and deep blue eyes. They began dating , and he courted her on and off for ten years until their marriage in 1946.

My father was of German heritage, the only son among the five

children of Venetia and John Anton Haardt, for whom he was named. Despite the hardships they faced, the Haardt family adhered

closely to Victorian standards and though they were poor, they appreciated the finer things. My Aunt Ida told me that sometimes

my grandmother prepared collard greens with fat back served in an ornate silver casserole dish. The children were carefully

instructed in etiquette, and received a good general education.

During his younger years, my father was a hell-raiser, in keeping with the Jazz Era of his day. One of his early

girlfriends was his childhood neighbor and fellow hell-raiser, Zelda Sayre, who later gained fame as the wife of writer F.

Scott Fitzgerald. After he married my mother, he changed his ways, curtailed his drinking and generally tried his best to

live a more responsible life.. For most of the twenty years I knew him, he worked six and a half days a week and rarely took

vacations. He started his one-man real-estate business more or less from scratch; his only employee was his secretary Mrs.

Wilkerson. With her bright red lipstick she reminded me of a brown-haired version of the comic-strip character, “Blondie.”

She also had a drinking problem, and my father often had to get her out of jail.

My father’s business strategy was to accumulate inexpensive properties that no one else

wanted and sit on them for future resale. As the years passed, he came to own so many properties around Montgomery that local

people would say, “If you went to the Moon you’d probably see a Haardt Realty sign.”

The biggest problem my father had was a constant struggle with alcohol. Once a year, more

or less, he would “check out” on a drinking binge for several weeks. He would surrender his car keys to my mother,

put on his pajamas and stay in his room drinking every day until my mother would “wean” him off the alcohol by

gradually decreasing his supply. I was told that Daddy was “sick” and when he received phone calls, I overheard

my mother saying he was on vacation.

When I was

three, my father began developing a subdivision called Haardt Estates, where he wanted only people of high society living.

He supervised the design and construction of our new home in the middle of its main street, which he gave his surname. Haardt

Estates became Montgomery’s most fashionable neighborhood in the 1950s; our spacious Greek Revival home was a showplace,

custom-built from architectural remnants my father salvaged from old mansions that had been demolished by fire.

My mother was sickly during the early years of my childhood.

She suffered from hay fever, recurrent hives and a heart murmur; everyone was concerned about her health. She tried hard to

play the role of a successful realtor’s wife, entertaining my father’s friends and wealthier clients at our home

and participating in local women’s groups such as the Garden Club; but his world was very different from the one in

which she had grown up. Years later, I began to realize how living up to her role put great pressure on her. The recurrent

health problems resulted from the stress of trying to fit in. Although she put on the proper appearance, I used to feel that

she was suppressing a deeply ingrained instinct for control… that she was almost acting a part…a submissive

part.

I was an only child, and stereotypically, I was overprotected.

My mother couldn’t let me cross a street by myself until I was eleven, and I wasn’t allowed to be alone without

a baby sitter until I was sixteen. Well into my adulthood, my mother tried to control me--and anyone else who would let her.

The most fearful form of control she exerted was forcing me to take enemas when I was very young, calling on Mammy Zora (who

tried to soothe me with calming words) to hold my ankles while she thrust injected the tube inside me. As a result, I suffered

with bowel problems until the birth of my son when I was forty. I had nightmares about enemas and enforced rape for years.

Like other upper-class white children of my generation in

the South, I took the presence of black servants for granted. When I was six months old, my mother hired a woman with a kind

demeanor and a formidable name, Zora Belle E. Quilla I.V. Carter Ellis. She was in her sixties, recently widowed, and had

never been able to have children of her own. She had spent most of her life farming; growing tired of such a hard life, she

was in dire need of a paying job. My mother introduced her to me as “Mammy Zora.” That’s what I called her

from the time I learned to speak. In addition to caring for me, she became the constant companion of my childhood.

Many people, of course, find the term “mammy”

offensive because of its racist connotations. I can’t defend that tradition; I can only make sense of my life. I was

a white child born in a racist culture, and in those early years I didn’t know any better than to address my nursemaid

by the familiar name to which she answered. As far as I was concerned, there was no fundamental difference between calling

her “Mammy Zora” and referring to my mother as “Mama.” Mammy Zora was like a second mother to me,

and in many ways I felt even closer to her than I did to my biological mother.

Mammy Zora was a tall woman with a warm smile. Her hair was braided in corn rows, wound into

a ball on each side of her head. She wore a neatly ironed white uniform and gold wire-rimmed eyeglasses. She lived with us

for years, until I was in my teens. Behind our house on Haardt Drive was a garage where our light-blue 1953 Clipper Packard

was parked, and directly above it was Mammy Zora’s simply furnished two-room carriage-house apartment. I remember her

old iron bed covered with a country quilt, and the large wooden rocking chair in which she loved to sit and rock. She always

carried a pack of Wrigley’s Spearmint gum in her black patent-leather purse, seemingly just for me. Whenever I went

up to her house for a visit, I went right to her shiny handbag to get my piece of gum. She welcomed those times, but Mama--trying

in vain to discourage me--always told me Zora’s purse was “dirty.”

Despite such comments and other not-so-subtle hints that she was in some way inferior to us,

I loved and respected Mammy Zora. She taught me to use the term “colored people,” and never to use the word, “nigger,”

a word I grew to detest.

After sixteen years of taking care

of me, Mammy Zora got too old to work. Almost eighty, she retired and moved back to the north side of town where she found

a small place for herself on Oak Street. I visited her often at her small new house. Even after I went away to college, we

corresponded regularly, and I’ve saved every letter she sent me.

Nowadays when I reflect back on my childhood and early youth, the warmest and most nostalgic feelings I have

are those for Mammy Zora. In 1975 she became ill; I was in Mexico at the time, and so deeply involved in my own turbulences

that I didn’t get back to Montgomery to visit her in the nursing home where she spent those final months. Had I only

realized how sick she was, I would have gone straight home to be with her. When I got the news of her death from my mother,

I sobbed even deeper and harder than I had when my own father died.

Several years later, I was making a purchase in a Montgomery department store when a woman turned to me after

she overheard me tell the cashier my name. She didn’t look remotely familiar to me. “Anton!” she said. “There

must not be too many women with that name. Did you know an old black woman named Zora Ellis?” I told her that she had

cared for me when I was a child. “My mother was in the nursing home with Mrs. Ellis right before she died, and they

shared the same room,” said the woman. Apparently she’d called out day and night, ‘My baby. I want my baby.’

It was so sad: we knew she didn’t have any children, we thought maybe she was out of her head. When we asked who she

was talking about, she said the ‘baby’ was called Anton . We didn’t know who that was, but it was obviously

someone who meant an awful lot to her. Anton, Mrs. Ellis surely did love you!” I hurried to the parking lot, broken

up in a million pieces.

When most people think of my hometown,

they associate it with the Civil Rights movement and the violence whites associated with it. From the mid-1950s until well

into the 1960s, Montgomery was the focus of a violent white backlash, but like many of the city’s middle and upper-class

white children, I was sheltered from the meaning of racial conflict. I didn’t know much about the protest meetings,

boycotts, or marches for equality, just as I knew little about what went on in the black neighborhoods.

I do recall the bus boycott, though--seeing large numbers of domestic servants walking to

and from their jobs in white neighborhoods, instead of congregating at the bus stops. In the mornings, uniformed black women

filed along Haardt Drive and Cleveland Avenue, heading to work, and in the late afternoons they could be seen going home on

foot. Before we moved into Haardt Estates we had lived on Cleveland Avenue, the main street these women took to reach our

subdivision. Many years later, after Montgomery’s political leaders belatedly began to acknowledge the importance of

what had happened during the 1950s and 1960s, this thoroughfare was renamed Rosa Parks Boulevard.

George Wallace, the staunch segregationist who was elected Governor in the 1960s, was a neighbor

of ours. After he retired as governor, he lived a few blocks away on Anton Drive. Wallace defied National Guard troops by

standing in the doorway of the administration building at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa to prevent the entry of

a black student to that institution.

My parents

didn’t talk much about any of this--at least not in my presence. Although they weren’t conspicuous about it, I

knew that they were as bigoted as most other white people in Alabama at the time. As I got older, I developed strong feelings

against the racial inequities that existed in the South and elsewhere around the country. But during my childhood and teen

years, I hadn’t matured enough to form a personal viewpoint on these issues, even though they were literally close to

home.

From an early age, though, I felt a spiritual kinship

with Mammy Zora’s people. I recoiled when I heard about students who would set out on weekends to “scare niggers,”

as if it were a sport like football or baseball. My cousins knew I wasn’t the one to listen to their “coon jokes.”

Since Mammy Zora was like a true mother to me, I felt as if her people are my people, and that we are all the same, despite

the color of our skin.